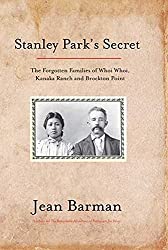

Rating: 7.7/10.

Stanley Park’s Secret: The Forgotten Families of Whoi Whoi, Kanaka Ranch and Brockton Point by Jean Barman

Book about the history of Stanley Park in Vancouver, specifically the people who lived there for several decades after the area was officially designated as a park. Today, Stanley Park is marketed as a pristine wilderness, but actually, many people’s histories were erased to create this image. Prior to the Europeans’ arrival, Whoi Whoi was a Squamish village containing about 50 people, situated in Stanley Park. In the 1850s, British officials started being interested in the area, constructing a mission, a mill, among other things, and wanted to relocate the Squamish people onto reserves elsewhere.

Around the 1860-1880s, a number of families settled around Brockton Point, the peninsula on the east side of Stanley Park. Kanaka Ranch was settled by a Hawaiian family who was brought to British Columbia to work and decided to stay. Joe Silvey was an ambitious entrepreneur from Portugal and settled on Brockton point, along with some family. Many of the men married indigenous Squamish women, giving birth to mixed-race children.

The City of Vancouver was officially incorporated in 1886, and the peninsula was designated as Stanley Park. A road was constructed around the peninsula, as close to the water as possible, and everyone living there was ordered to be removed. Around this time was when the Canadian residential school system started, and most of the children (of mixed-race indigenous ancestry) were taken to residential school. In residential school, many of them died, and those who survived were left with disintegrated family connections. By the 1910s, most of the pure indigenous people had moved away (except for one elderly woman), only a few people (second generation children of the original immigrants living at Brockton Point) refused to move and wanted adequate compensation for their property.

The city went to court against the habitants of Brockton Point in 1922. The law required that the defendants prove their family lived there continuously for 60 years (since 1862), so the two sides went to court, digging up old maps and calling up elderly witnesses. The trial was not an easy one for the defendants, since only their side needed to show the burden of proof, and testimonials by indigenous people were seen as unreliable. The case went all the way up to the Supreme Court, who ultimately decided that the defendants did not show sufficient proof of continuous habitation for 60 years, and thus they lost the case. After winning the legal battle, though, the city was in no hurry to physically remove the tenants, which was not a very high priority task for them, thus, as the park modernized, people continued living there for several more decades. The last man, Tim Cummings, lived in Stanley Park until his death in 1957.

Overall, this book tells an interesting piece of local history, a few families whose existence in the park is now almost completely erased. In an ironic of events, the city erected fake indigenous villages and totem poles, while simultaneously trying to evict real indigenous people living just a few dozen meters away. The mixed race ancestry of the inhabitants meant that they were too white to be considered truly indigenous.